The morning of December 6, 1917 was like any other day in

Halifax, Nova Scotia. Halifax had been founded by the British military as a fortress to protect their interests against the French back in the late 1700s thanks to its large and deep natural harbor as well as its strategic location.

Early 20th Century Halifax

With World War I raging in Europe, the factories, foundries and mills in both Halifax and nearby Dartmouth were working at full capacity, keeping the harbor busy with with shipping convoys taking goods and supplies across the Atlantic, destined for the war effort in Europe.

Ferries to and from Dartmouth, located on the opposite side of the harbor, civilian shipping, as well as fishing boats and pleasure craft all competed for space with the military shipping traffic on the harbor adding to the congestion.

Meanwhile, the French vessel the Mont-Blanc was loaded with 228,000 kilos of TNT, 2.1 million kilos of wet and dry picric acid, a toxic substance used in the making of munitions and explosives, 223,000 kilos of Benzol, a highly flammable liquid similar to gasoline, and "guncotton", a highly flammable substance used in firearms, all of which made the Mont-Blanc a floating bomb of the highest order.

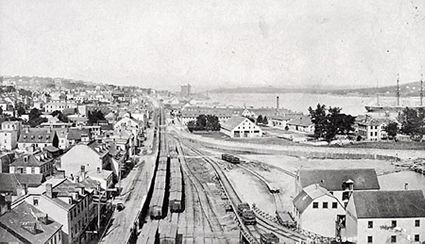

The Mont-Blanc

Unable to cross the Atlantic solo due to the risk of a German u-boat attack, the Mont-Blanc sailed out of New York for Halifax in order to join a convoy of other ships congregating in Halifax Harbour in the interests of safety. While the ship arrived in late afternoon on December 5th, it was too late in the day to enter the harbor, as the anti-submarine nets had been closed for the night, forcing the Mont-Blanc to spend the night outside the harbor.

Meanwhile inside the harbor, the Belgian relief ship Imo was forced to delay its scheduled departure that day due to the supply of coal for its boilers arriving too late for it to leave for New York in order to collect emergency supplies for civilians in war ravaged Belgium prior to the harbor gates being closed.

At 7:30 in the morning on December 6th the navy opened the gate in the nets, allowing the Mont-Blanc to head into the harbor, traveling at a speed of four knots, under the limit of five knots. At the same time, the Imo headed toward the Narrows to begin its voyage south. As the Imo increased its speed to seven knots, it encountered the first ship entering the harbor. That incoming ship went against the usual rules of passing on the left. The two ships exchanged horn blasts to signal their intent, which resulted in the Imo passing the other ship on the right, putting the Imo on the wrong side of the harbor in the Dartmouth channel.

Once past the first ship, the Imo continued to steam along on the wrong side of the channel, allowing it to avoid a tug boat towing a pair of barges which had just pulled away from the Halifax shore on the right of the Imo.

The Mont-Blanc and the Imo were now in the same channel as they continued to travel toward each other. The Mont-Blanc blew its whistle first to signify that it had the right of way and would be maintaining course, implying the Imo would have to move to the right to clear the way. The captain of the Imo however, had other thoughts, and blew his whistle twice to signify his intent to hold his course. The Mont-Blanc then moved slightly to its right closer to the Dartmouth shore to give the Imo additional room for clearance, hoping the Imo would respond in kind by moving to its right in order to give the two ships adequate distance between them for safe passage. When the Mont-Blanc again blew its whistle once, the Imo responded with two blasts of his horn, indicating it would not be changing course.

The sailors who knew what the repeated signals meant realized trouble was brewing and gathered to watch the two ships. Finally, as the Mont-Blanc and the Imo were bearing down on each other, the Mont-Blanc turned hard left into the center of the channel to avoid a collision with the Imo, as it could not move any further toward shore for fear of running aground while loaded with such dangerous cargo.

Unfortunately for all concerned, the Imo now finally chose to change course by reversing engines, which swung the ship to its right - and into the path of the Mont-Blanc. If only one of the ships had made its evasive maneuver, nothing more than a close call would have been the result. However, they both were now aimed for the same spot and the resulting collision caused the Imo to penetrate nine feet into the hull of the Mont-Blanc at 8:45 AM. The Imo then pulled away to extricate itself from the Mont-Blanc, causing enough sparks to ignite the lethal combination of picric acid and vapors from the ruptured drums of benzol, producing an uncontrollable fire at the forward end of the damaged Mont-Blanc.

Fearing an immediate explosion, the captain of the Mont-Blanc ordered the crew to abandon the ship, which was spewing a large column of oily, black smoke. As the public gathered on the streets or stood at the windows of their homes to watch the spectacular fire and exploding barrels of benzol rocketing into the air.

The rescuers, as well as those on the shore, had no idea of the danger contained inside the Mont-Blanc, as any outward warnings of the dangerous cargo in the form of red flags were not displayed on the Mont-Blanc for fear of drawing unwanted attention from the Germans while at sea. As boats rushed to their assistance, the crew of the Mont-Blanc attempted to warn them off as they rowed furiously ashore in their lifeboats, but they were unable to be understood, as the crew spoke only French as they reached the Dartmouth side and ran for the woods and to safety.

The hastily abandoned ship was now not only ablaze, but also adrift and moving toward Halifax's Richmond neighborhood and into Pier 6, which then caught fire as well. The boat was then met by the Halifax Fire Department, with its one motorized truck and a dozen horse-drawn wagons, who were all unaware of the ship's highly dangerous contents.

And then it happened.

The Mont-Blanc erupted with a force stronger than any man-made explosion in world history prior to the atomic age. The ship shattered and was blown sky-high, 980 feet into the air. White hot pieces of its hull came falling back to Earth as lethal shrapnel rained down all over Halifax and Dartmouth. A 1,140 pound piece of the ship's anchor landed 2 1/2 miles away while the Mont-Blanc's gun barrel flew over three miles, landing clear across the harbor in Dartmouth.

This photo was taken just seconds after the explosion of the Mont-Blanc

The fireball rose over 6,200 feet over the harbor, symbolizing the hell that had just descended on the area. The smoke from the fire reached 20,000 feet while buildings shook and items fell off of shelves as far as 80 miles away with the shock wave being felt 200 miles away as 400 acres in the immediate vicinity were completely destroyed by the blast.

Homes, apartments, business and the sugar refinery were all destroyed in an instant. Every building within a 10 mile radius, 12,000 in all, were badly damaged, if not destroyed.

Additionally, the water immediately surrounding the ship was evaporated by the intense heat of the explosion, which momentarily exposed the harbor floor! The shockwave from the blast sent water rushing violently outwards, creating a wave that spread toward both shores, rising as high as 60 feet. The wave carried the Imo onto the shore on the Dartmouth side of the harbor as the tidal wave washed up three blocks into the city.

The Imo, washed ashore on the opposite side of the harbor

Over 1,500 people died instantly, while 9,000 were injured by not only the blast, but falling debris from the shattered ship, collapsing buildings and shards of flying glass, which blinded 38 people with roughly 600 more suffering eye injuries while standing at their windows watching the initial blaze.

Many of those who survived the initial blast now had to hang on for their lives as the water rushed up onto the shore where they had gathered, claiming more victims who were in shock or injured and unable to withstand the surging waters. Miraculously, all but one of the crew of the Mont-Blanc survived the disaster.

Since it was wintertime, fires broke out all over as stoves, lamps and furnaces throughout the area were toppled, igniting blazes fueled by the debris, which claimed even more victims throughout the region, in part due to the majority of the firefighters having died in the initial blast, as well as the lack of standardized equipment from town to town which hampered the efforts when fire hoses could not be coupled together.

The damaged Halifax Exhibition Building

More fatalities occurred the following day when a blizzard dumped 16 inches of snow on the region, which included those still trapped in the rubble of collapsed buildings, those not yet tended to and those susceptible to the cold, as homes no longer had glass in the windows to contain any heat. In the days that followed, people moved into churches, temporary shelters and even railroad boxcars - anywhere warm and dry.

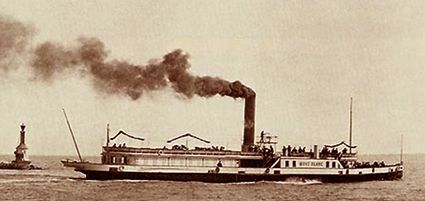

Halifax after the snowfall

The final death toll was 1,950 with 1,630 homes destroyed in the explosion and fires. 6,000 people were rendered homeless and 25,000 lacked adequate housing. Industry was essentially gone, as was the workforce.

In 1994 a study was conducted comparing 130 major, artificial, non-nuclear explosions by a team of scientists and historians and they concluded that "Halifax Harbour remains unchallenged in overall magnitude as long as five criteria are considered together: number of casualties, force of blast, radius of devastation, quantity of explosive material and total value of property destroyed."

The piece of the Mont-Blanc anchor, which was hurled over 2 miles by the blast

Nine days after the disaster, the first exhibition game in NHL history was contested between the Montreal Canadiens and the Montreal Wanderers played a benefit game for the victims of the explosion at Halifax Harbour.

The first NHL season was only four days away, as the league had only just been formed the previous month when the owners of the Canadiens, Wanderers, Ottawa Senators, Toronto Arenas and Quebec Bulldogs, in an effort to rid themselves of contentious, difficult and abrasive fellow National Hockey Association owner

Eddie Livingstone.

Livingstone, who owned both the Toronto Shamrocks and Toronto Blueshirts, had multiple disagreements with the NHA and his fellow owners over many matters, including his ownership of two clubs, which gave him two votes in league matters. He feuded with the Wanderers owner

Sam Lichtenhein in particular, and at one point Lichtenhein offered Livingstone $3,000 to simply close up shop and walk away from the NHA, while Livingstone countered with a $5,000 offer if Lichtenhien would do the same!

Today's featured jersey is a 1917-18 Montreal Wanderers Harry Hyland jersey. At their November, 1917 annual meeting, the NHA voted to suspend operations, supposedly "due to the difficulty in running a five team league", only to meet again in a weeks time, only this time without Livingstone, to form a new five team league, the National Hockey League, which was the NHA minus Livingstone but with the Toronto franchise in new hands.

The Wanderers, who had been formed back in 1903, had first taken possession of the Stanley Cup in 1906 by winning the ECAHA playoffs and won seven cup challenges and four league titles over the next five seasons. They then fell on hard times after entering the NHA, losing the only playoff series they contested over the next eight seasons. Their final three NHA seasons saw a string of fourth and fifth place finishes, thanks in part to the loss of players off to serve in World War I, putting the team in a fragile financial position as interest in the club among the anglophones waned.

Once the inaugural NHL season began, the Wanderers, the team of Montreal's minority English speaking population, defeated Toronto in a thrilling 10-9 opening night contest attended by just 700 fans despite the offer of free admission for military personnel and their families. They were then manhandled by the Canadiens 11-2. Ottawa then took two games in a home and home set by scores of 6-3 and 9-2, with the second game begin played on December 29, 1917.

The 1917-18 Montreal Wanderers

Four days later on January 2, 1918, the Wanderers were scheduled to play the Canadiens again, but a fire that began in the Montreal Arena's ice making plant, spread and burned the arena down to the ground. Team owner Lichtenhein had already made a request from the other clubs to loan the Wanderers better players to field a more competitive team in hopes of attracting more fans, but when the plan was rejected by his fellow owners following the fire, and with his club dealing with the loss of their home arena, Lichtenhein disbanded the club on January 4, ending the Wanderers fourteen year history.

The aftermath of the Montreal Arena fire

Harry Hyland was leading the Wanderers in scoring in 1917 when the club folded. He had a ten year career in hockey, playing first for the Montreal Shamrocks in 1908. He joined the Wanderers for two seasons, including as a Stanley Cup champion in 1910, before spending the 1911-12 season with the New Westminster Royals.

He returned to the Wanderers in 1912-13 and played six more seasons with the club with whom he averaged over a goal per game, scoring 158 goals in 134 games with a high of 30 in 18 games in 1914. His greatest single game came in 1912-13 when he scored 8 goals against Quebec.

Following the demise of the Wanderers, he joined the Ottawa Senators as a playing coach to finish the season and his career. He was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1962.

Today's featured jersey is a 1917-18 Montreal Wanderers Harry Hyland jersey worn by the Wanderers for their brief time in the brand new National Hockey League. The Wanderers debuted white sweaters with the red stripe around the center adorned with a shield containing a white "W" for the 1905 season and it would remain their only sweater throughout the rest of their days.

Had the Wanderers survived, it is hard to imagine they would have ever changed their style in a manner similar to the Canadiens or Detroit Red Wings. So closely was their distinctive sweater associated with the club, that the team was often referred to as "the Redbands".

Today's first video is a reenactment of the Halifax Explosion, which illustrates the incredible devastation of the largest man made detonation on Earth prior to the atomic age.

Today's second video is actual newsreel footage of the devastation and rescue work immediately following the disaster.

Thank you for posting this. I lost three family members in this disaster. I had no idea the NHL did a fundraiser for the victims but I think it's great that they did. I'm going to share the article with my family as well.

ReplyDelete