Mighty Muskox thrive in the elements of northern AlaskaWhen the Mighty Muskox first played in USA Hockey’s Adult Classic in 2009 in Anchorage, Alaska, it marked the first time the team had played hockey indoors.

“It was like a kid in a candy store,” said captain Mitch Erickson. “The lighting was great. The ice was perfect. The corners were smooth. I play goal and if a shot was above the boards, I could see it.

“The rink also was bigger and was a whole lot warmer. We actually rented ice time before the tournament just to get used to it.”

The Muskox — named after the Artic animal that is considered to be a descendant of the woolly mammoth — made their third trip to the tournament earlier this year and captured the Bronze (30-plus) Division championship.“We had two teams, one in the Adult Bronze that won and another in the Novice Division that bombed out,” Erickson said. “The majority of us are in our 40s and 50s. We have two players in their 30s, so that’s where we have to play. There were a lot of greybeards out there. I’m sure they would have qualified for an over-40 team, too.”

The Mighty Muskox’s enthusiasm for playing indoors stems from their unique home base.“We’re located approximately 550 miles northwest of Anchorage just below the Arctic Circle near the Bearing Sea with no access to roads,” Erickson said. “One of our players, Ken Hughes, rode his snowmobile 75 miles one way just to play.

“He moved to Nome last year but for a number of years he rode his snowmobile. We call him Kenny ‘Hockey’ Hughes.”

The Mighty Muskox built their own rink — outdoors — and they feel it’s North America’s westernmost hockey rink, indoor or outdoor.

“We were the only team that won [at the 2011 Adult Classic] that plays on outside ice,” Erickson said. “We have trouble playing indoors because we usually warm up shoveling snow and scraping the ice.

“We don’t have a Zamboni, but we have our own homemade mop system, which is more of a spray bar hooked to a garden hose, and we drag it.

“After we built the rink, we maintain it with volunteer labor and equipment,” continued Erickson. “A guy named Charlie Painter is a key volunteer who keeps the rink up and running.”

Obviously, Nome will never be confused with Miami when it comes to weather. And, understandably, that’s a story all by itself.

“We had to use heavy equipment … a big 966 front-end loader and caterpillar with a bucket on it — 31 times last year to clean the snow off the ice,” Erickson said. “That was a record. But it’s become par for the course the last few years. If we get a good snowstorm, it will fill the rink to the top of the boards.

“But, usually within 24 hours, we’re ready to play again.”

There’s also the matter of temperature — which is another way of saying the Mighty Muskox don’t play in “balmy” weather.

“It could be 10 above with 25 mile-per-hour winds, which equates to 45 below,” Erickson explained. “A lot of us will be out there when it’s 20 below zero. We also have an informal club that plays at 30 below. I’ve never played in 30 below, but I have played when it’s been 29 below.”

If that sounds like standard procedure in Alaska, think again.

“When we go to Anchorage we’re asked ‘You guys actually play outside, in the wind and the cold?’” Erickson said. “They think we’re whacked out.

“Our town’s population is about 3,500 and we only have 10 miles of roads in the winter. It takes a lot of motivation to leave a warm place in 20-below weather.”

The genesis of the Mighty Muskox occurred 10 years ago when the son of St. Cloud, Minn. natives Ron and Jane Brown accepted a teaching position in White Mountain, a small village about 65 miles East of Nome.

“There was an article in the Nome Nugget newspaper about Ron and Jane sending equipment to their son to start hockey there,” Erickson said. “Somehow, we connected with the Browns and they ‘adopted’ us.

“They’ve been great supporters of our program as has the Hockey Zone in St. Cloud. They’ve sent us used youth equipment and skates on several occasions. I also recall that St. Cloud Cathedral sent us equipment once, too.”

Once the rink was built, according to Erickson, more guys came in and they’ve played hockey ever since.

“We have everybody from beginners to a guy who had some pro experience,” Erickson said. “There are a few who were born in Minnesota and played youth and high school hockey there in the 70s. But most everyone else just picked it up, especially the local boys.”

What’s given Erickson a great deal of satisfaction is that the two youngest players, Banner Romensko and Daniel Stang, come back from college during their holiday break and play for the Mighty Muskox.

“That’s the best reward for all the time we’ve spent putting this rink together,” said Erickson.

“Next year we’re going to have a Novice 21 team because then these kids who are 21 can play with us. We’ll have 58-year-olds with 21-year-olds.”

Thursday, February 2, 2012

2010-11 Nome Mighty Musk Oxen Jersey

Nome, Alaska was in the news recently when it was cut off from the world due to a massive storm last fall, which prevented the normal supply of fuel from reaching the remote town of 3,500 inhabitants.

Threatened with running out of fuel before it made it through the rest of the winter, it necessitated the U. S. Coast Guard icebreaker Healy to cut a path through 300 miles of sea ice up to 8 feet thick to enable the Russian tanker Renda to resupply Nome with fuel for it's snow plows, ambulances, fire trucks and police vehicles as well as heating 1,000 homes in a area where temperatures regularly drop to -40º F.

The Healy began it's journey on January 6th, sometimes gaining just a few miles a day, due to it being the only active ocean-going Coast Guard ice breaker in the Arctic as well as being classified as just medium in size. It arrived 10 days later on the 16th and then 1.3 million gallons of fuel had to be transferred through hoses across a half a mile of the ice covered harbor into Nome.

The Renda and the icebreaker Healy after their arrival at Nome

But this wasn't the first time Nome had been cut off from the rest of civilization and in need of supplies. Located just two degrees south of the Arctic Circle, Nome had been icebound since July of 1924 and reliable air travel would not yet be an option for the better part of ten years. The only rout for mail and needed supplies was via dog sled traveling along the Iditarod Trail, a 950 mile route which originated in Seward, Alaska and ran across several mountain ranges and the vast Alaska Interior before reaching Nome, a journey normally expected to take 25 days when delivering mail.

Shortly after the departure of the last ship of the season, a two-year old child in the nearby village of Holy Cross became the first person to display symptoms of diphtheria, which was first diagnosed as tonsillitis. Diphtheria is extremely contagious and can survive for weeks outside of the human body, and the child died the following morning. Another fatality occurred on December 28th followed by two more children dying. Finally, on January 20th, the first case of Diphtheria was diagnosed and the town's only doctor, Dr. Curtis Welch, had only expired diphtheria antitoxin from 1918 on hand. The boy died the next day.

The next day another child was diagnosed as being in the late stages of the disease. In an attempt to save her life, she was given the antitoxin, yet she died later the same day. Now realizing they had a serious situation on their hands, the town council was summoned by the Mayor George Maynard and a quarantine was enacted and on January 22nd Dr. Welch sent a telegram alerting the outside world an epidemic was about to break out and they were in need of the antitoxin.

Two more people died by the 24th and 20 more cases had been confirmed with 50 more at risk. In all, 10,000 people were under threat in northwest Alaska, and without the antitoxin, the death rate would be close to 100 percent.

A plan was put into place to have a pair of sled dog teams, one leaving from Nome led by Norwegian Leonhard Seppala, who had made the run to Nulato in a record setting four days and was a three time winner of the All-Alaska Sweepstakes sled dog race. Seppala's team was led by Togo, a dog as famous as his owner for his leadership, intelligence and ability to sense danger.

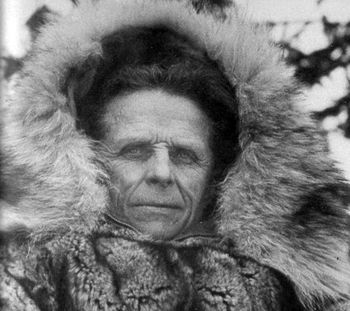

Leonhard Seppala and Togo

While not large enough, a supply of the antitoxin big enough to hold off the disease was located in Anchorage, which was delivered to Nenana from Anchorage by rail on January 27th while a larger supply would arrive in Seattle, Washington on January 31st.

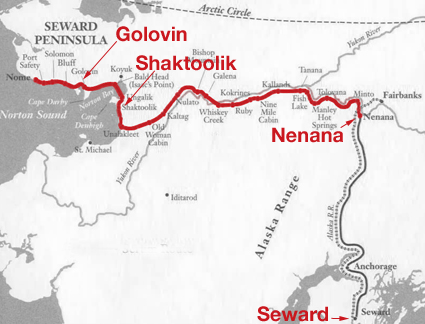

A relay of the best drivers and teams was arranged to deliver the serum from Nenana across the interior to Nulato, where Seppala would be waiting to make the return trip to Nome, a full distance of 674 miles. Telephone calls and telegrams called back the drivers who were out on their various mail routes and assigned them to their positions along the route. "Wild Bill" Shannon was the first musher in charge of the 20 pound package, leaving the train station in Nenana at 9 PM on January 27th in temperatures of -50º F. Bear in mind, in Alaska during late December, the sun does not rise until 12 noon and sets at 4 PM, for just four hours of daylight each day.

Forced off the trail and onto the even colder river due to damage to the trail by horses, he arrived in Minto at 3 AM with his face black from frostbite and suffering from hypothermia with the temperature now at a staggering -62º. After a four hour rest, Shannon set out once again and arrived in Tolovana at 11 AM in bad shape to hand the serum over to Edgar Kallands, whose hands were reportedly frozen to the sled's handlebar when he arrived in Manley Hot Springs at 4 PM in -56º weather, needing warm water poured over his hands to free them.

From there, several native Athabascan's took their turns, Dan Green, Johnny Folger on January 28th and Sam Joseph, Titus Nikolai, Dan Corning, Harry Pitka, Bill McCarty and Edgar Nollner on January 29th before George Nollner delivered the antitoxin to Charlie Evans at Bishop Mountain at 3 AM on January 30th.

Meanwhile in Nome, the two new cases had been diagnosed on January 29th despite the quarantine due to the contagiousness of the disease. News of the crisis was now front page news in the lower 48 states from San Francisco to New York.

Evans braved the cold weather, and the loss of two of his dogs to frostbite, arriving at 10 AM. The next to take a turn was Tommy Patsy, who was followed by a man nicknamed "Jackscrew" and then Alaska Native Victor Anagick who in turn passed the package on to native Myles Gonangnan in Unalakleet along the shore of Norton Sound at 5 AM on January 31st. Gonangnan had to brave whiteout conditions and gale force wind chills of -70º to arrive in Shaktoolik at 3 PM, where Henry Ivanoff was waiting in case Seppala was not there.

The number of cases in Nome had risen to 27 and all hope now lied with the dogs and their heroic drivers.

Seppala and his team, led by Togo, had travelled 170 miles from the 27th to the 31st, leaving in -20º temperatures in Nome, only to arrive in Shaktoolik by taking a shortcut across the sound in temperatures of -30º and windchills of -85º thanks to an approaching storm.

Ivanoff and his team ran into a reindeer and were tangled up shortly after leaving Shaktoolik when Seppala, thinking he was still on his way to Nulato 100 miles away and unaware of the change in plans to hand over the serum to him in Shaktoolik, passed by Ivanoff, who shouted to him that he had the serum in hand.

Having reached Ungalik, and with the news of the epidemic having worsened, Seppala set out to cross the exposed open ice of the sound in the dark, braving the -85º windchill, arriving at Isaac's Point on the other side of the sound at 8 PM, having traveled 84 miles that day. After resting, he and his team once again set out at 2 AM into the full power of the storm with temperatures of -40º and winds of 65 mph. They crossed the 5,000 foot elevation of Little McKinley Mountain and arrived in Golovin on February 1st at 3 PM.

Leonhard Seppala

The serum was then passed on to Charlie Olsen, who was blown off the trail and suffered frostbite putting blankets on his dogs in windchills of -70º. He arrived in Bluff at 7 PM on that night in rough shape to hand off to Gunnar Kaasen, who waited three hours for the storm to break, only to find it getting worse and left into a headwind at 10 PM before drifts blocked the trail.

He travelled through the night through drifts and over the 600 foot Topkok Mountain in visibility so bad he sometimes could not see his dogs! He actually overshot Solomon by two miles and decided to keep going, at one point having his sled tipped over by the winds, which caused the cylinder with the serum to become buried in the snow. Kaasen then suffered a case of frostbite of his own when he had to use his bare hands to free the stuck cylinder.

He eventually reached Point Safety at 3 AM actually ahead of schedule only to find the next driver asleep and with his team unprepared. With his lead dog Balto and the rest of the team performing well, Kassen chose to keep on going for the final 25 miles to Nome, arriving on this date in 1925 at 5:30 AM with his cargo intact, without a single vial of the serum broken.

Balto and the team that delivered lifesaving serum to Nome

The antitoxin was thawed out by noon and ready for treatment to begin after the dog teams had travelled 674 miles in 127 1/2 hours in extremely cold temperatures in near-blizzard conditions and gale force winds in what would become known as "The Great Serum Race" or "The Great Race of Mercy".

A map of the route of the serum, with the dog sled route in red with Seppala's leg from Shaktoolik to Golovin highlighted. Note how it crosses the sound at one point, shaving a day off the trip.

The epidemic was now under control and the next shipment arrived by sea on February 7th with a third traveling again by dog sled on the 15th.

All the participants of the first dog sled relay received letters of commendation from President Calvin Coolidge, gold medals and $25 from the territory of Alaska.

Kassen and his dogs became celebrities, touring the west coast of the United States for a year, including starring in a movie about the relay. A statue of his dog Balto was placed in Central Park in New York City in December of that year, while the real Balto and team became part of a sideshow until being rescued and given a permanent home at the Cleveland Zoo, where Balto lived until 1933 before being mounted and put on display at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History.

The statue of Balto in Central Park

History now recognizes Seppala and Togo as the true heroes of the relay, as they covered the longest distance and most hazardous conditions, making a round trip of 261 miles, forwarding the serum 91 miles, almost double the distance of any other team. Seppala and Togo also went on tour across America, including 10 days at Madison Square Garden in New York. Togo lived until 1929 and is now on display at the Iditarod Museum in Wasilla, Alaska.

Togo at the Iditarod Trail Museum

The extreme weather conditions this winter, with temperatures in Nome reaching -40º, were reported to have cracked hotel pipes and even reduced the turnout at the Mighty Musk Oxen's pickup hockey games.

From USAHockey.com:

Today's featured jersey is a 2010-11 Nome Mighty Musk Oxen jersey. Actually, we should say "jerseys", as half the team is wearing jerseys emblazoned with the old Minnesota North Stars "N" logo, recycled for "Nome", with the stars of the big dipper (as seen on the flag of Alaska) above, while the other half of the club has jerseys with "Mighty Musk Oxen" arched over an illustration of a Muskox!

Today's first video is a tribute to the Great Serum Run of 1925, which includes some film footage of those involved.

Next, an interview with the Executive Officer if the icebreaker Healy as it made it's way to Nome.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment

We welcome and encourage genuine comments and corrections from our readers. Please no spam. It will not be approved and never seen.